Across the high, open uplands of the North Pennines - in County Durham, Cumbria and South-West Northumberland - work has been quietly underway for two decades. It is work that doesn’t announce itself easily: no new buildings, no grand infrastructure. Instead, it involves blocking old drainage channels, rewetting exhausted ground, and allowing slow ecological processes to resume.

This year marks twenty years since the North Pennines National Landscape team began a sustained programme of peatland restoration - an effort that has now brought around 50,000 hectares of damaged peatland under restoration, attracted £49 million in investment, and helped establish the region as a national and international reference point for landscape-scale peat recovery.

Peatlands are among the planet’s most underestimated ecosystems. Although they cover just around 3% of the Earth’s surface, they store more carbon than all the world’s forests combined. In healthy condition, peatlands act as long-term carbon sinks, water filters, biodiversity reservoirs, and natural flood regulators.

When degraded - often through historic drainage, over-grazing or burning - they become sources of carbon emissions rather than stores, releasing centuries of accumulated carbon back into the atmosphere.

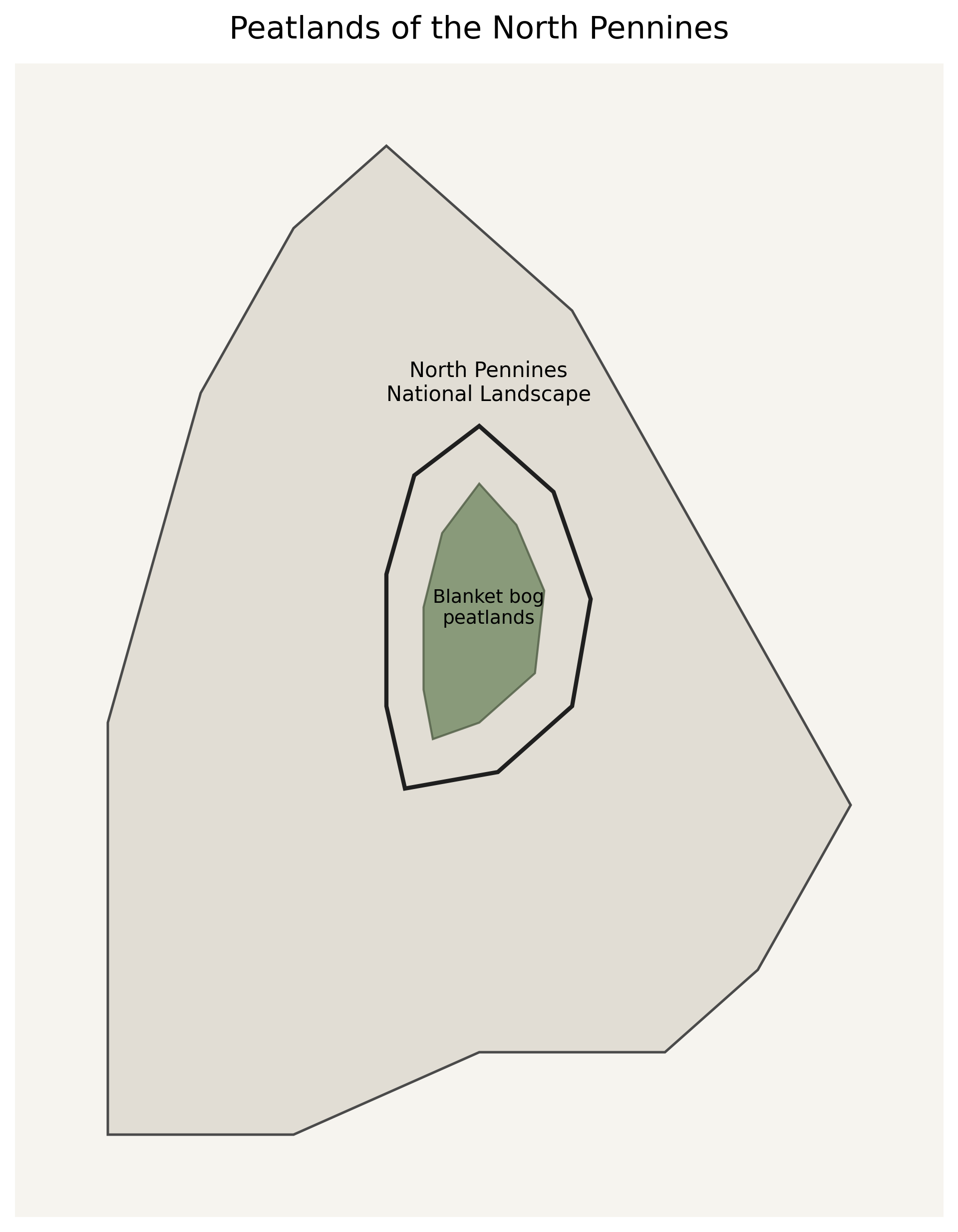

The North Pennines is home to the largest contiguous area of blanket bog peatland in England, making the condition of its uplands nationally significant for climate, water, and nature recovery.

Blanket bog is a rare type of peatland found mainly in cool, wet, upland landscapes. Unlike valley bogs or fens, blanket bogs form a continuous “blanket” of peat across hills and plateaus, often covering entire watersheds.

They develop extremely slowly. Over thousands of years, waterlogged conditions prevent plant material - mostly mosses such as Sphagnum - from fully decomposing. This partially decayed vegetation accumulates as peat, locking away carbon that would otherwise enter the atmosphere.

The UK holds around 10–15% of the world’s blanket bog, making it globally significant. England’s largest continuous area lies in the North Pennines.

When healthy, blanket bogs:

When damaged or drained, they can dry out, erode, and begin releasing carbon - turning a climate asset into a liability.

Peatland restoration in the North Pennines began in 2006 as a three-year project, initially funded by the Environment Agency. At the time, large areas of upland peat had been heavily modified by drainage “grips” - channels cut into the peat to dry land for agricultural use.

Early work focused on blocking these grips, raising water tables, and allowing blanket bog vegetation to re-establish. Over time, techniques evolved, expertise deepened, and the work expanded - moving from isolated interventions to a coordinated, landscape-scale approach.

Today, peatland restoration is a core part of how the National Landscape is managed for people, nature and climate, with a mix of public funding, private finance and grant support sustaining long-term recovery rather than short-term fixes.

“Grips” are narrow drainage channels cut into peat soils, mainly during the 19th and 20th centuries, to dry land for agriculture and grouse management.

While effective at draining land, grips disrupt the natural hydrology of blanket bogs. Water drains too quickly, peat dries and cracks, vegetation dies back, and carbon stored over millennia can be lost in a matter of decades.

Grip blocking is a restoration technique that reverses this process. Using peat dams, wooden barriers or stone structures, the channels are blocked at intervals, slowing water flow and raising the water table.

The effects are gradual but profound:

Grip blocking is now considered best practice in upland peatland restoration and forms the backbone of much of the work in the North Pennines.

A defining feature of the programme has been its collaborative approach. Restoration has been delivered in partnership with landowners, land managers and local contractors, embedding the work within working landscapes rather than separating conservation from land use.

Paul Leadbitter, Peatland Programme Manager with the North Pennines National Landscape team, has led the work since its early days: “All of the work we have done has been carried out in partnership with landowners and land managers from across the North Pennines. It’s this collaborative approach that has made it possible to restore such large areas of damaged peat.”

One of the earliest restoration sites was on Raby Estate, which covers a large area of Teesdale in County Durham and has a longer history of peatland management.

Duncan Peake, Chief Executive of Raby Estates, describes the value of long-term collaboration: “That partnership has resulted in better decision making, more creativity, and improved delivery through enhanced learning. Together we’ve been able to deliver climate, ecological, hydrological and economic benefits for the North Pennines.”

While carbon storage is often the headline, restored peatlands deliver a much wider set of benefits. Rewetted bogs slow the movement of water through catchments, helping to reduce flood risk downstream. They filter water naturally, lowering treatment costs, and create conditions for a rich mosaic of plant and animal life to return.

Over time, healthy peatlands also support local economies - through skilled restoration work, monitoring, and the growing field of nature-based solutions.

This broader impact has drawn international attention. Dianna Kopansky, Global Peatlands Initiative Coordinator at the United Nations Environment Programme, describes the North Pennines work as a model for others: “Their efforts over the last two decades are a blueprint for how organisations can restore peatlands at a landscape scale - and a reminder of why continued funding is so critical if nature is to thrive.”

The North Pennines programme is also part of the Great North Bog, a collaborative initiative bringing together six delivery partners across Yorkshire, the North East and the North West. Together, they are restoring peatlands at a scale that contributes meaningfully to the UK’s climate and carbon sequestration targets.

Seen in this wider context, the last twenty years in the North Pennines represent not a finished project, but a foundation - proof that long-term, place-based environmental repair is possible when funding, expertise and trust align.

As climate pressures intensify, peatlands - slow, wet and patient - may yet prove to be among the North’s most valuable assets.

Header Image: Peatland restoration site at Murton Fell in the North Pennines