There are around 16 million disabled people in the UK. That’s one in four of us.

And yet only 7% of people working in the arts identify as disabled.

Only 35–50% of UK theatres are considered fully accessible. Just 25% regularly offer captioned or audio-described performances.

These are not marginal gaps. They are structural exclusions.

And for many young Deaf, Disabled and neurodivergent people across the UK - including here in the North - they are daily reminders that cultural spaces were never designed with them in mind.

That is the context in which The Access Manifesto was born.

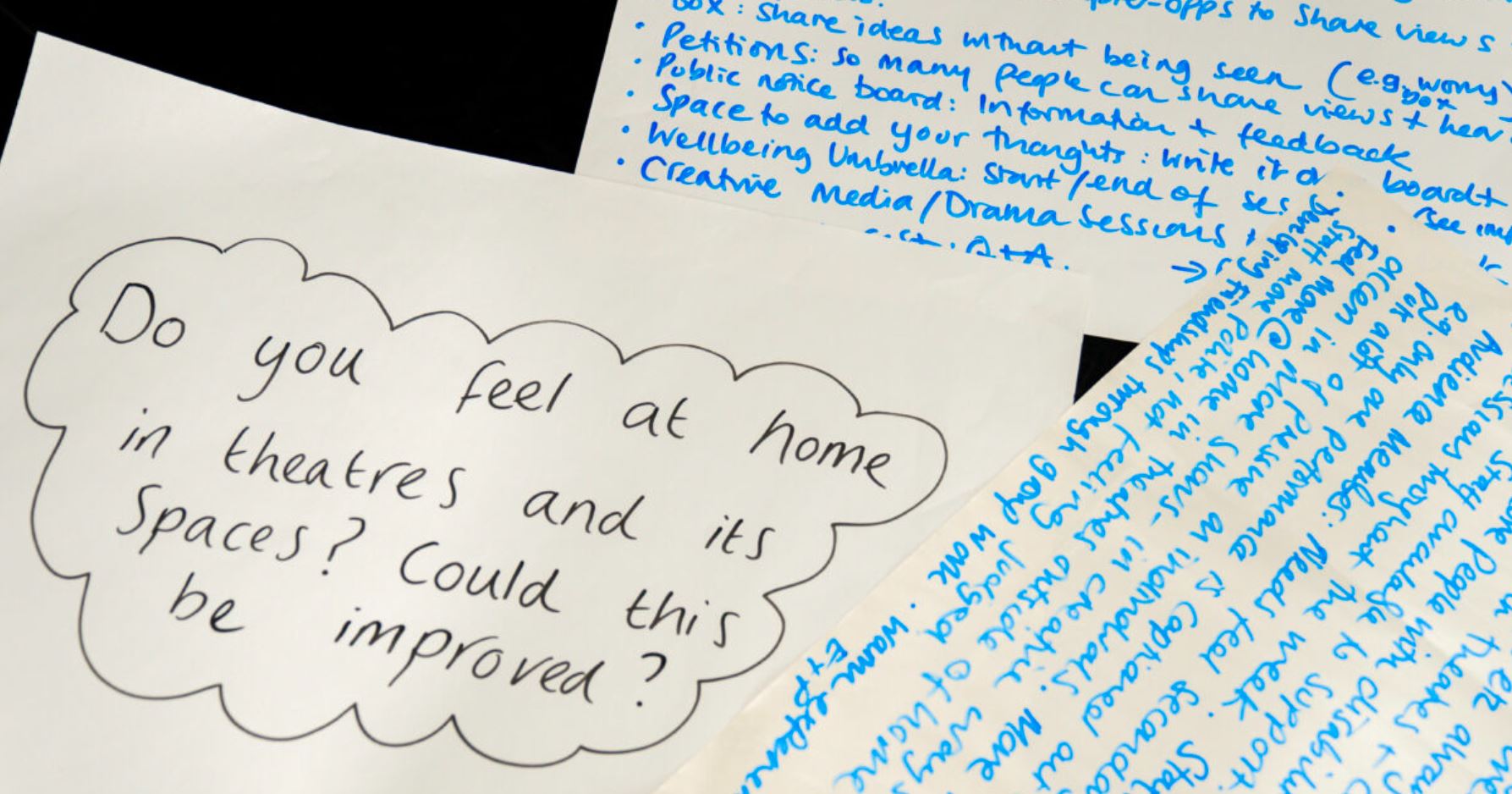

The Access Manifesto is not a policy document drafted in a boardroom.

It is a response.

Developed by over 60 Deaf, Disabled and neurodivergent young people and young adults, led by 20 Stories High (Liverpool), Graeae Theatre Company and Tip Tray Theatre, the Manifesto is a practical, step-by-step call to action for arts organisations to fundamentally rethink accessibility.

Its co-author, Maisy Gordon, does not speak in abstract terms. She speaks from experience.

She describes being locked out of a theatre with no accessible entrance.

Being infantilised because she uses a wheelchair.

Losing work because access adjustments were dismissed.

And once, becoming physically stuck in an inaccessible backstage corridor mid-show.

“Experiences like these are not only physically harmful, but psychologically damaging,” she writes. “They reinforce the message that Disabled people were never considered, never expected, and never truly welcomed.”

That sentence lands heavily.

Because it forces the sector to confront something uncomfortable: This isn’t accidental. It is systemic.

The UK population is approximately 24% disabled. The arts workforce is 7% disabled.

Disabled employees in the arts are 20% less likely to advance to senior roles compared to non-disabled colleagues (Arts Council England).

Representation on stage and in leadership remains disproportionately low. Access provision - from BSL interpretation to relaxed performances - is inconsistent. Digital access remains uneven. Recruitment practices remain exclusionary.

The problem is not lack of talent. It is lack of structural commitment.

And that’s where The Access Manifesto positions itself differently.

And yet:

Accessibility is not a niche concern.

It is a question of who gets to belong - and who quietly disappears.

The Access Manifesto maps out an eight-point plan. It is direct. Practical. Achievable.

It calls for:

These are not abstract aspirations. They are operational demands.

The document also dismantles persistent myths:

Myth: Accessibility only benefits disabled people.

Fact: Ramps help parents with prams. Captions help non-native speakers. Clear signage helps everyone.

Myth: We’ve never had complaints, so we must be accessible.

Fact: Many simply stop coming.

Myth: Accessibility is about buildings.

Fact: It includes websites, recruitment, rehearsal spaces, backstage corridors and internal culture.

This is not about compliance. It is about belonging.

There is something deeply fitting about this movement being driven from Liverpool and the North.

20 Stories High has long championed culturally diverse, working-class young people, mixing rap, beatboxing, dance and theatre to tell authentic stories. Their collaboration with Graeae Theatre Company on High Times and Dirty Monsters exposed many of the access challenges that young disabled artists continue to face.

The Manifesto extends that work beyond performance into systemic change.

Since its launch in late 2024:

This is momentum. But it is early.

Accessibility is often framed as expensive. But exclusion has a cost too.

When nearly a quarter of the population is effectively underserved or overlooked, the arts sector is not just failing morally - it is failing economically, creatively and culturally.

Disabled art is not niche. It is “joyful, powerful, innovative, and full of talent,” as Maisy writes.

But it should not fall solely on disabled artists to fight their way in. “Arts organisations must take responsibility,” she says. “Commit to access as a fundamental part of practice, not an afterthought.”

The next chapter is already unfolding.

Tip Tray Theatre - a disabled-led company based in Knowsley - is developing A Space For Us, rooted in two of the Manifesto’s key pillars: Open Doors For All and Welcoming Spaces.

This is about practical transformation. Reimagining how venues welcome audiences, artists and staff. Challenging environments that are unintentionally hostile. Shifting culture from performative inclusion to genuine invitation. It is grassroots, lived, urgent. And it is not waiting for permission.

For our MagNorth readers - for artists, producers, funders, cultural workers, educators - this is not someone else’s issue. It is a mirror.

The Access Manifesto is not radical because it asks for extraordinary measures. It is radical because it demands that accessibility becomes normal.

Because if one in four people are disabled, accessibility is not a special feature. It is infrastructure.

The arts in the North pride themselves on authenticity, community and representation. The question now is whether that commitment extends fully to disabled people - not just in audience development strategies, but in leadership, rehearsal rooms, backstage corridors and commissioning decisions.

“This means so much to me, and millions of others,” Maisy says. “We are so ready for change.”

The manifesto is not the end of the conversation. It is the line in the sand.

There’s a phrase that crops up again and again in arts funding applications, mission statements and strategy documents: welcoming.

We welcome audiences.

We welcome new voices.

We welcome difference.

But the Access Manifesto quietly asks a harder question:

Who are we actually built for?

Because welcome isn’t what you say at the door.

It’s whether the door was ever designed with someone in mind.

For many of us working in the arts - especially in the North of England - there’s a genuine belief that we’re “doing our bit”. That we’re more grounded, more community-facing, more honest than the institutions we sometimes side-eye down south.

And often, that’s true.

But the testimonies behind The Access Manifesto remind us that good intentions don’t cancel out exclusion. In fact, they can sometimes mask it.

If someone doesn’t complain, we assume everything’s fine.

If a space looks accessible, we assume it is.

If disabled artists aren’t applying, we assume the pipeline’s the problem.

What the Manifesto does - gently but firmly - is interrupt those assumptions.

It asks us to notice who isn’t in the room.

Who stopped coming.

Who never felt invited in the first place.

This isn’t about blame. It’s about attention.

Accessibility isn’t a bolt-on. It’s not a special performance or a once-a-year initiative. It lives in rehearsal schedules, in recruitment language, in how front-of-house staff are trained, in whether someone feels safe asking for what they need - or exhausted by having to explain it again.

And perhaps most uncomfortably, it lives in power:

who gets listened to,

who gets paid,

who gets promoted,

who gets to decide what “good” looks like.

The Access Manifesto doesn’t pretend this work is easy. But it refuses the idea that it’s impossible.

It offers something rare in cultural conversations: a way forward that is practical, collective and led by those most affected.

For those of us who care deeply about the arts - not as an abstract ideal, but as a lived, local, human practice - that should land as an invitation, not a threat.

Not: you’ve failed.

But: you could do better - and here’s how.

The North has always prided itself on straight talking, mutual care and getting stuck in.

If that’s true, then listening to the Access Manifesto - really listening - feels like the least we can do.

Read. Reflect. Act: The Access Manifesto resources are available via 20 Stories High and Graeae Theatre Company. The question now is what we do with them.